Canberra is, in many ways, a bookish city, not the least because of its material book history. Having discovered an historical ‘moment’ when two book cultures intersected and acculturated in Canberra in the mid-1980s, I’m going to look at the effect of that moment for material book practices both within Canberra and in Australia generally. I suggest that, after a long period of decline following the rapid uptake of digital desktop publishing, the time is ripe for a renaissance of the material book in Canberra.

Keywords: artists’ books – papermaking – bookbinding – Canberra – private press – letterpress – printmaking – materiality

In the national mythology of Australian cities, Canberra comes across as being too neat, too boring, too planned to be vibrant. Stuffed shirts, greedy politicians: a bunch of hardback books. We are told there is a palpably bookish air to the place, but not the warm, cultured prose of Melbourne or the short-story bite of Sydney: more like a long straight row of Hansard. There is a sub-myth: that Canberra is like one of those fake books with the centre cut out that hides something far more interesting — but only the people who live here can access it. I think both myths are being challenged. Canberra has long been a seriously creative city, but it is the myths that people often believe. There is a book-centred, trail of events that shows a side of the city’s creative history that I’ve been slowly sniffing out. What follows is incomplete and subjective. I am telling you tales, tales that I have been told by people who know people, tales from places I have inhabited, sometimes well after they were part of this story.

1: Finding a moment

Canberra has long been more than just archives and libraries. It has had a relatively integrated material book culture compared to other major Australian cities. By material, I mean the nuts and bolts of making a book: papermaking, design, bookbinding, image-making (especially printmaking), and textual production in both senses of the word: printing and writing. By culture, I mean activity: individuals working alone and together, creative collaboration between printers, binders, artists and writers to produce book work. Canberra is a small-town city; large enough to have multiple activities, but small enough for those activities to be connected and to overlap.

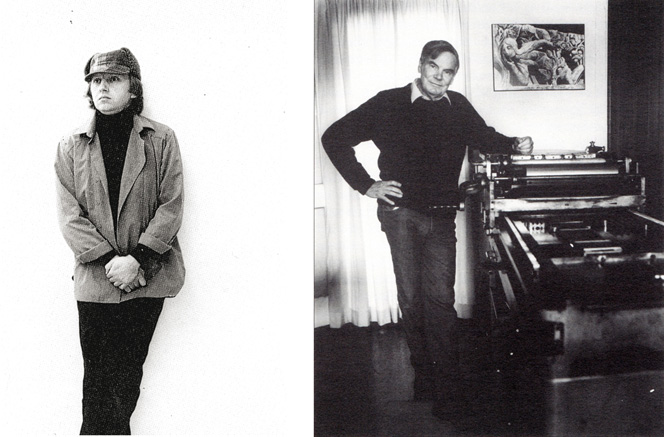

In the 1970s the National Library of Australia hired ex-Angus & Robertson and Ure Smith commissioning editor, Alec Bolton, to be their first Director of Publications, with a brief to showcase the collection’s treasures. Bolton had just been living in England where he had learned to print with letterpress, and his spare time from the NLA job was spent establishing his own private press, the Brindabella Press (Richards 1993: 11-12). Bolton, inspired by the British fine press movement, started with a table-top press and a tray of type and slowly accumulated more letterpress equipment and confidence, eventually producing 23 elegant limited editions, each undertaken with all the attention to detail and production values that a book could possibly want without appearing overblown. Bolton was married to poet Rosemary Dobson, who was socially connected to poets such as AD Hope, David Campbell and Judith Wright, mighty poets who had such a grip on the Canberra poetry scene that it didn’t have an experimental poetry movement in the 1970s. Instead they had the ANU Poets’ Lunch, where old and young poets wrote ‘light’ or ‘occasional’ poems to each other, sponsored by the local legend Jim Murphy who was in charge of the university cellar. Two such young poets, Alan Gould and David Brooks, whether inspired by Bolton or not, started their own private press, the Open Door Press, and printed limited edition broadsides and pamphlets of their contemporary poets every weekend in a garage.

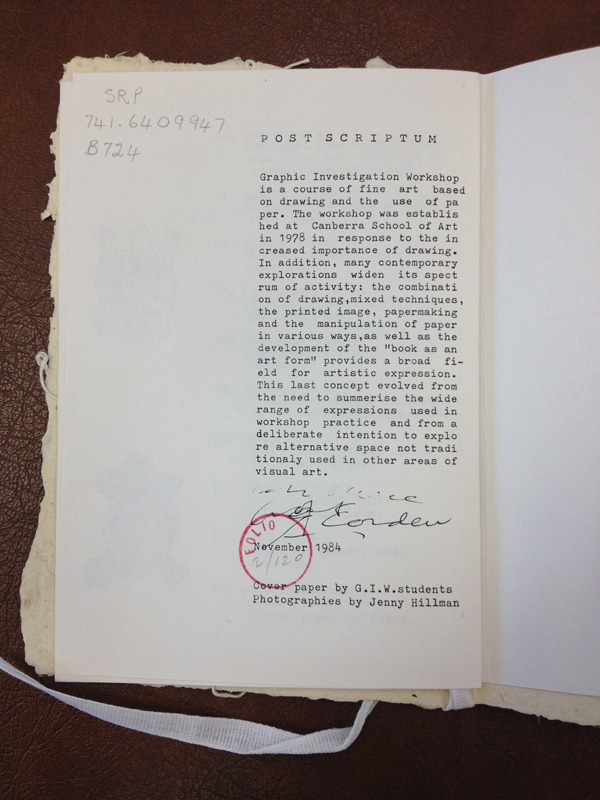

By the end of the 1970s Canberra had a School of Music and a School of Art. The School of Art’s first Director was Udo Sellbach, a German printmaker, who invited a number of European practitioners to head up the school’s Bauhaus-inspired vision of art and craft workshops with community outreach (Agostino 2009: 27). He created a workshop called the Graphic Investigation Workshop (GIW), centred around the philosophy of ‘drawing and the use of paper’ (Herel 1984), and invited Czech artist Petr Herel, who had exhibited at the Ruth Prowse Gallery in Canberra several times during the early 1970s, to be the head.

Herel came to Canberra imbued with a very different notion of the book: it was experimental, with the page seen as a space rather than a surface. He also brought with him a love of experimental French writing: Mallarmé, Michaux, Baudelaire, Rimbaud. Under Herel’s guidance, using enthusiastic local staff and exotic visiting artists, the daily business of the GIW was to take drawing and the material book seriously, to break down the barriers between process and form and to work with the form of the book creatively. The book was a vessel of exploration, something that could hold, showcase, accentuate and extend every kind of mark-making that art can produce. Image and text held equal weight, and handset letterpress (and later polymer plate) was readily available to students without constraint. Many of the books produced were unbound; this was partly because of Herel’s cultural heritage, but also because the workshop didn’t have proper bookbinding equipment, so bindings were often rudimentary. Many of the books also paid utter disregard to tradition or binding and even to quality: they were sometimes unopenable objects, or cassette tapes, or pieces of bone.2

These two men, Herel and Bolton, represent two very distinct creative publishing cultures. One operated at the rise of artists’ books as a legitimate art genre in its own right, and the other was one of the last great press operators at the twilight of the Australian private press movement — which continues to stagger along, but is being subsumed by the term ‘fine artists’ books’. Both men moved in different, although — because this is Canberra — overlapping, social circles. They were never more than nodding acquaintances, but they have many similarities. They took their own book work, and the processes involved in making books, very seriously. They cultivated creative and skills-based collaborations to achieve the outcomes they desired, and in doing so motivated many others to do the same. They were both inspired by traditions of the northern hemisphere, but while they personally worked within those traditions, they encouraged a local sensibility in their mentoring of others. They both liked to share knowledge, and were very generous to students and fellow enthusiasts. And they operated in Canberra over the same time period: around the mid-1970s until 1996, when Bolton died of a heart attack whilst still in full production mode and Herel retired because of his own heart problems, and moved to Melbourne where he still makes books.

I’ve been wondering how the diverse artists’ book culture of today developed around the country in the mid-1980s, well before the rise of the internet helped to disseminate international trends. I was sure that the GIW had a solid influence upon it, but I couldn’t really work out how (apart from the graduates moving out into the world, but few of them actually went on to have book practices). When I was at the Melbourne Codex Australia symposium in March 2014, I talked about the book-making activities of the GIW as if it were well known around Australia in its own time, but in truth for the first ten years of its existence, it was only really being watched by Canberra-based national institutions like the National Library and National Gallery, as well as by galleries who knew Herel’s work, but not by other art schools. This was a point really brought home to me by a paper given by artist’s book maker and collector Monica Oppen, who had been learning printmaking in Sydney in the late 1980s and early 1990s, desperately trying to make books rather than straight prints, and never once hearing about these people in Canberra, only 3 hours away, who were making artist’s books on a daily basis.

If you look at the records of the State Library of Queensland (http://www.slq.qld.gov.au/resources/art-design/artists-books: one of the first Australian institutional collections of artists’ books), you can see that Australian artist’s books existed in the 1970s but they tended to be low-tech and conceptual, either produced offset with black & white photographs or hand-made with stamps, photocopiers, letraset, Ronio-style methods and typewriters. They look a lot like today’s zine culture, an observation I made when reading Gary Catalano’s survey, The Bandaged Image (1983). Soon after his book was released, there seemed to be a visible shift in the books of the SLQ collection, away from the conceptual: a plunge into materiality, a break-out of works that seem inspired by the crafts movement that had run concurrently with the conceptual art movement at the time. Try it for yourself: trawl through the SLQ catalogue chronologically. There are about four pages of the more conceptual 1970s/early 80s books by the usual suspects like Ian Burn, Robert Jacks and Richard Tipping with titles like ‘Black lines, hand-stamped’ and ‘Everybody should get stones’: cheap and cheerfully stamped, photocopied and stapled — and then suddenly, in 1984 there is a shift in the list: printmaking and papermaking books. Dianne Longley, from South Australia was one of the earliest, followed by a few Petr Herel books, some books by papermakers including one by Katharine Nix, plus a humorous book by Helen Wadlington, a Canberra bookbinder who also worked with Alec Bolton.

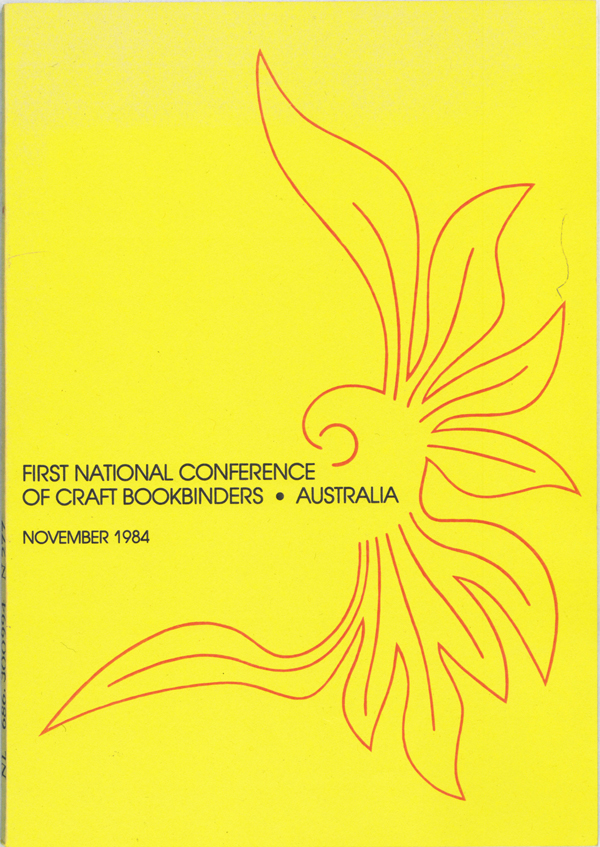

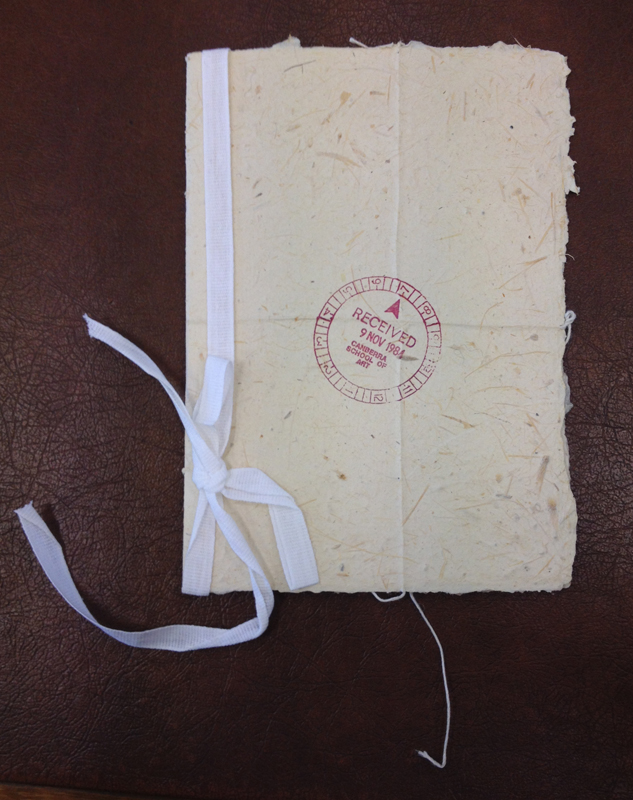

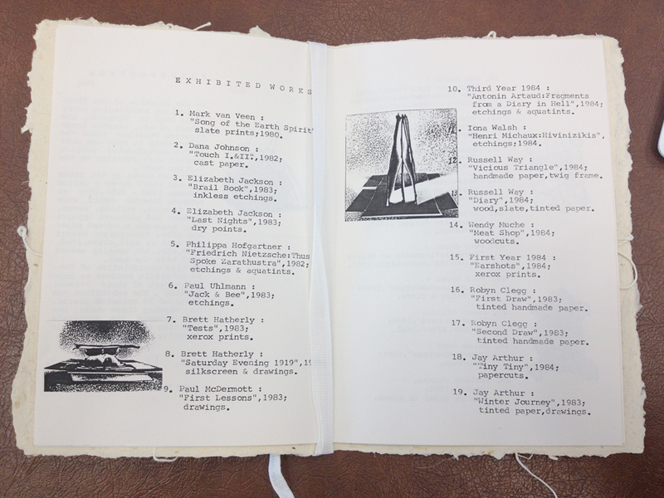

I realized, looking at these catalogue dates, that I’d long known of one historical moment when those two seemingly oppositional book circles — the nascent makers of artists’ books as they are now (structurally and/or conceptually challenging everything about the book as an object) and the traditional craft bookbinding practitioners — cross-pollinated, and that was in 1984, in Canberra, initiated by Canberra people. It was a conference held at the Canberra School of Art, organized by the very new Canberra Craft Bookbinders Guild (Rogers, Shannon, Wootton, 1984). And in response to it, Petr Herel organized the very first exhibition of experimental book work done by his workshop, especially for the visitors (Herel, 1984).

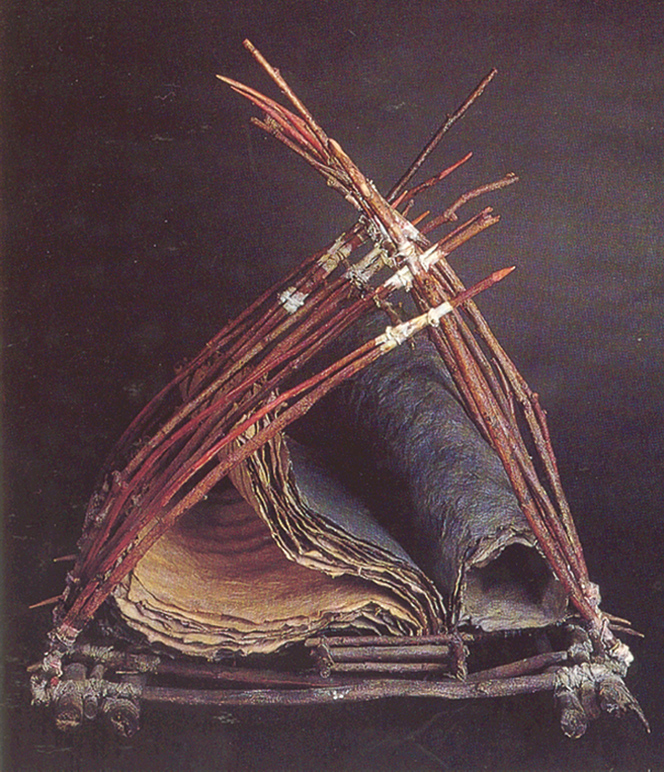

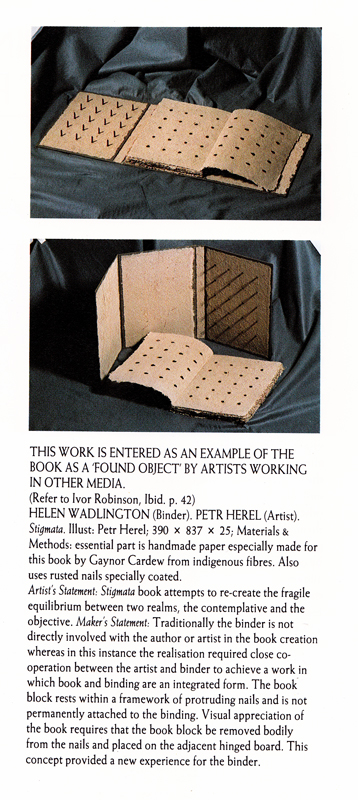

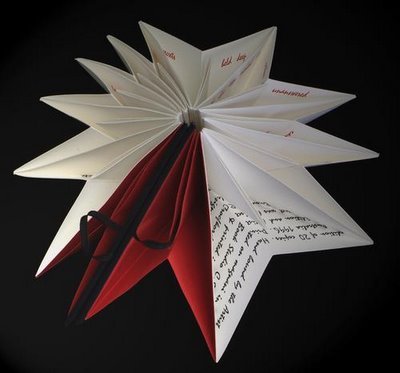

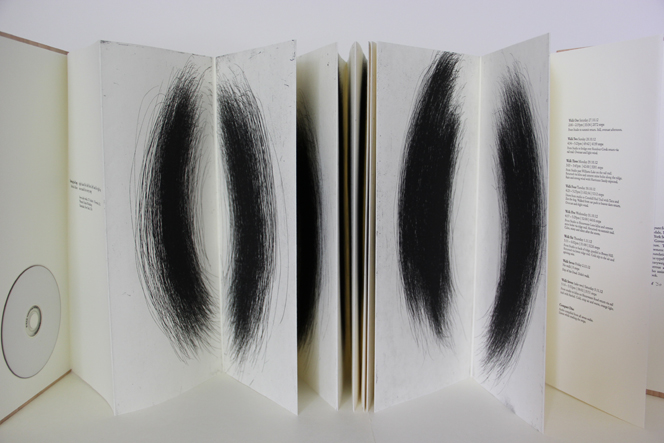

A lightbulb went off in my head. Picture the scene: a quire of traditional craft bookbinders (commercial and designer), coming together from all over Australia for the very first time, discussing subjects like leather paring and tooling, edge gilding, adhesives, headband sewing — and being shown work like this:

And this:

And this:

As Herel related to me by phone in October 2014, his exhibition consisted of 25 book-works, ranging from classic French-influenced unbound volumes through to very experimental drawing and sculptural pieces, laid out on white-paper-covered tables in one of the GIW rooms. The binders viewed the works in a group as the staff and students carried on their activities around them. When asked about the reactions he experienced, Herel replied that ‘the older ones were startled. They had an air of defiance: ironic smiles. They treated us as amateurs.’

I have proof of their bewilderment. In association with the conference, the National Library of Australia hosted an international craft bookbinding exhibition, complete with catalogue (CCA 1984). Despite there being a whole section of the catalogue devoted to international alternate books presented by UK binder Ivor Robinson and his polytechnic students (admittedly, shoved to the back of the book), the tone of the printed ‘introduction’ to Petr Herel’s collaborative fine binding (not included on anyone else’s work) is one of utter bewilderment (1984: 35).

Sharp eyes might have noticed that I have mentioned Gaynor Cardew twice so far: as an example from the GIW exhibition and in this fine binding collaboration. Until the early 1980s, papermaking was exactly that: making paper, usually in the service of printing, but by the beginning of the 1980s it had joined other crafts in searching for conceptual validity in the art world. Most experimentation was inspired by painting in the form of 2D paper-pulp drawings and prints. In 1983, twenty-four Australian papermakers (including Penny Carey Wells, who shared this information with me by phone in Oct 2014) attended a major international papermaking conference in Kyoto, where they saw a large number of very haptic and conceptually material artist’s books. The Craft Australia Yearbook 1984 has a chapter on papermaking that shows papermakers from all over Australia working conceptually in sculptural and flat graphic modes, but there are also book works, made by Gaynor Cardew and fellow Canberran Katharine Nix (Wilson, 1984: 91–101). These two women were important: they were influenced by Herel’s workshop and in turn influenced it by their work. They connected Herel’s finer art scene, the Canberra crafts scene and more grass-roots political visual organisations such as the Megalo screenprinting facility. (The yearbook has a chapter on book arts too, but at this point of time none of the examples have any connection to the kinds of books shown in the papermaking section; they are all traditional bindings, with many of the images by a Canberra designer binder, Brian Hawke (Hudson, 1984: 77-89), again demonstrating that Canberra was already a hub of material book practice.)

Conference participants were taken, as part of a general tour of local book crafts workers, to visit Cardew’s own workshop at the Old Canberra Brickworks in Yarralumla, which was described in the conference proceedings as ‘a series of buildings in various states of repair. It resides in a paddock with lots of weeds, concrete pipes and other useful debris’ [1984: 73]. The space would have been interesting: Cardew was a cartoonist, political poster printer and papermaker who worked with Petr Herel and his students right from the start of GIW, helping them to make paper, and artist’s books. Cardew tempered Herel’s formality with her enthusiasm for paper-play and structural experimentation; she was close friends with Canberra fine binder Helen Waddlington, which explains the collaborative fine binding from the NLA exhibition, and also how she was included on the tour. Cardew and Nix eventually managed to carve out a space in the art school for a papermaking studio which was established in 1990 and survived until about 2009 (Agostino, 2009: 166). 3

That small, intense GIW exhibition by a handful of students and teachers contained work that had never been seen in this country before. This is complete speculation, but I would be willing to bet that many of the people who went to the bookbinders’ conference either went home and tried something fun as a result of the GIW showcase, or showed the GIW catalogue, with its raw handmade paper covers and insouciantly typed and photocopied pages, to their colleagues and friends. Cardew and Nix did their own evangelism, showing their books at other conferences, like the Textiles Fibre Forum, where experimental papermaking found its home. The influence went both ways: Jay Arthur, a GIW student, attended the conference, and no doubt most of the students in the workshop went to the NLA fine binding exhibition, picking up ideas about book traditions.

In 2001, looking retrospectively at his 20 years of teaching, Petr Herel called the artists’ book ‘an instrument of collaboration’. In fact, his whole workshop was an instrument of collaboration. Unlike other schools where generations of students learned from a small group of teachers, Herel had a constant stream of visiting artists who would teach for a term or semester, each bringing something with them: a new technique, a fresh perspective. Thus you would get batches of enthusiasms: a wave of mezzotint practitioners, a crush of aquatints, followed perhaps by a craze for limp leather bindings, or paper-casting from plaster moulds. There was no regular look or brand for the output apart from the overarching themes of drawing and books. And the books were their own ambassadors. As I said, few of the students went on to make books after they graduated, but their student works made an impact.

This book, Concrete Poetry by GIW student Bernadette Crockford, was bought by the SLQ, and instantly became a poster-child for their collection. Bernadette was very keen to learn craft bookbinding, and was encouraged to do an internship with Canberra binders John and Joy Tonkin, whose business is called Book Arts Canberra. John was also at the 1984 conference, and he tolerates unusual books but only if they’re made well. He loathes concertina books. John is from the Alec Bolton craft circle, but he interacted with the Herel camp when asked. He in turn encouraged a number of local binders, many of whom also do artists’ book bindings, such as Robin Tait, who also worked with Bolton.

2. How that moment grew into a field of wonder

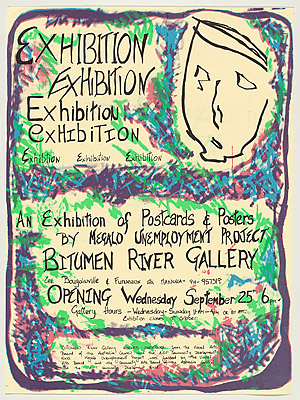

Canberra’s material book culture seemed to grow exponentially from the early to mid-80s. In 1984, the National Library exhibition of designer bookbindings in conjunction with the conference would have interested the art school’s new Leather Workshop, which was established in 1981 in response to the boom in craft. Testament to this boom in crafts is the gallery listings in a copy of the Canberra Times from 1986 (the earliest I could access). I counted a grand total of 30 galleries in the free listings, ten of which were dedicated craft galleries. Many of the art galleries eventually merged to stay alive, like the poetically-named artist-run initiative Bitumen River Gallery which is now CCAS Manuka. The National Gallery’s ‘highlights’ blurb in the paper states ‘Highlights include: Australian Printmaking 1773–1985; Plastic, Rubber and Leather: Alternative Dress and Decoration’ (Canberra Times 8/5/86)

Printmaking is hot in 1984. The art school printmaking workshop is large and active, and graduates are socially engaged, enabled by the new access workshop Studio One in Kingston and the less comfortably situated but very active screenprint facility, Megalo (Wallace 2013).

Studio One is a new initiative by two printmaking graduates, Meg Buchanan and Dianne Fogwell (Grishin 1994). It allows printmakers, who often depend upon heavy, expensive equipment, to stay in the area upon graduating and to build up their practice until they can afford their own studio. Megalo was set up in 1980 at the Ainslie Village site in a hot, crowded tin shed and is operated as a collective headed up by Alison Alder and Colin Little. Politics around this time are grim on the community level, and Megalo provides an affordable and colourful way to mobilize the streets. Anyone can print, but if they just have a good idea, Megalo can also help by printing for them. This being pre-the desktop publishing era, they also print promotional posters for music, theatre, galleries and other organizations.

Because it is the pre-desktop publishing era,4 options for creative text publishing are: analogue printmaking processes like screenprint; etching and lithography; handset letterpress (also a printmaking process, really); offset printing using camera-ready copy; rub-on letraset; stencils; typewriters; ronio machines; and photocopiers— all very labour-intensive. This next few years is a window of time when anyone graduating as a graphic designer is immediately unemployable unless they can manifest computer skills to replace the manual skills they’ve been taught. But computers are expensive and the software is complicated. Bookbinding and letterpress are still being taught as trade skills, and Canberra has a healthy number of trade bookbinders and printshops. There is no self-government in the ACT. At this point the art school is funded independently by the Federal Education Board and is not part of ANU, so student assessment is a simple and effective pass or fail. Bob Hawke is PM, and it is the era of Neville Wran and Joh Bjelke-Petersen. Medicare is brand new. Hey Hey it’s Saturday shifts to Hey Hey it’s Saturday Night. Megalo has a lot to be angry about.

Flash forward to 1996. Canberra has been busy. We got self-government in 1988 by all voting for the ‘No Self Government’ Party. The local TAFE, renamed Canberra Institute of Technology (CIT), is still teaching bookbinding and printing but the print industry is moving on — fast. Australia, around this point, is the world’s leader in early adoption of new print technology. Neale Wootton, the NLA conservation bookbinder who helped organize the 1984 conference, is teaching the CIT’s Book Craft night class, and he encourages his students to get involved in the Canberra Craft Bookbinding Guild. The Guild has members who are actively interested in the work coming out of the GIW, and so they slowly start to branch out from traditional binding methods, to the soundtrack of elderly grumbling.

The GIW — now interacting with a strong comic book subculture that has developed in Canberra (Hill 2007) — is nevertheless winding up as Petr Herel’s health declines. The Leather Workshop didn’t last long (there’s only so much you can do with the stuff) and when it was dismantled, Herel negotiated with the school to turn it into a book studio, a dedicated room filled with type and presses where students, staff and visitors could work together. Upon his retirement, the Printmaking workshop merged with the GIW to become one large workshop called Printmedia and Drawing, headed up by Sydney artist Patsy Payne, who had produced a number of artists’ books as part of her print practice.

Fogwell and Buchanan had stepped back from Studio One in 1990 to pursue new projects. Fogwell increased her teaching in the GIW and established her own press and studio, Criterion Press, in Braidwood, commuting to Canberra daily. Fogwell, who makes both formal and informal artist’s books, managed to persuade the school to keep the Book Studio as a separate entity from Printmedia, ostensibly as an income generation facility for the school. It became the Edition + Artist Book Studio, with a strong collaborative and mentoring philosophy, where students worked alongside professional artists to edition books and prints. Buchanan set up her own studio and became head of Foundation Studies at the art school.

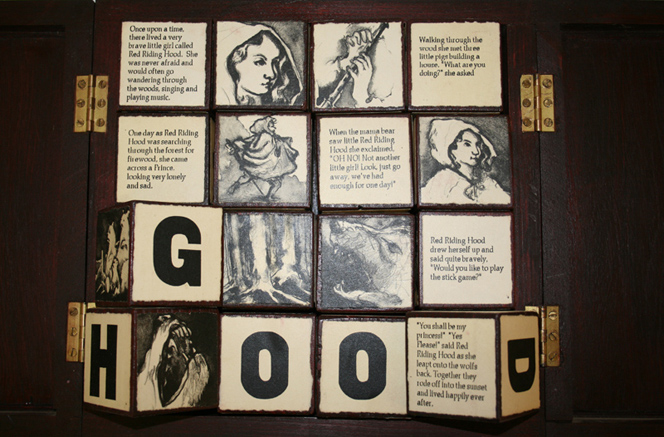

Studio One incorporated and expanded, provides a space for GIW graduate Les Petersen to house his letterpress and type, enabling Raft Press to exist (Grishin 1994). Raft Press is the love child of the Graphic Investigation Workshop. Petersen is dedicated to the concept of artists’ books and to the process of collaboration. For the seven or so years that Raft Press exists, it is extraordinarily prolific, working with the print facilities at Studio One and collaborating with papermakers like Katharine Nix to help artists from Australia and New Zealand produce 30 books for the 1992 Book Project, and a further 34 books for the 1994 iteration titled The River Styx (Sticks). Both exhibitions travelled internationally. Petersen works on the projects as a textual production enabler, working with each artist to realize the book that they want to make, like Jan Hogan’s Little Red Riding Hood (1993).

The papermaking scene is healthy and vibrant: Katharine Nix’s paper studio in O’Connor is active and the generation of students that she and Cardew train now teach in the Papermaking Studio at the School of Art. A number of them go on to work with Indigenous papermaking collectives and other community groups.

Nationally, the artists’ book scene is starting to ramp up. Noosa Regional Gallery starts an annual book show. Noreen Grahame starts a series of artists’ book and multiples fairs (Grahame, Kirker & Hoffberg 1996). The SLQ is buying bookwork, as is the State Library of Victoria, although the latter tends towards the finer end of the spectrum. A council librarian in Mackay works out that she can use her book budget to buy artists’ books when the gallery money runs out. By the time anyone notices, she’s built up a collection of 300 books, which inspires negotiations for a purpose-built space to house them. Works-on-paper award exhibitions like the Fremantle Print Award are starting to accept books as entries.

Alec Bolton’s death in 1996 seems to coincide with a sharp downturn in the private press movement. However, his working methods also mirrored the conditions of the decline. Increasingly interested in the design of his books rather than the exact means of production, Bolton had been shifting over the years from hand-set letterpress, to machine-set and cast slugs of type, and in the year before he died he had jumped aboard the now-established desktop publishing train, learning to use Pagemaker in order to produce polymer plate layout for his press. The freedoms that desktop publishing brought to book-making just cannot be underestimated. Anyone can lay out a book and print it themselves, although at this time colour printing isn’t quite there yet. A lot of awful books came out at this point, but conversely a lot of publishing opportunities were grasped. Ginninderra Press is started by Stephen Matthews, dedicated to printing local writers, many of them emerging from the University of Canberra. The UC Foundation Librarian, Victor Crittenden, jumps at the chance to reprint historical literature, starting his Mulini Press in 1990 at a cracking pace. By the time he dies in June 2014, Mulini Press had published 108 books.

Flash forward again, to 2006. The materiality of the book seems to be declining (worldwide), and efforts to fight this seem forced as energy shifts in other directions. The art school has been firmly integrated into the ANU and budgets are tightening. Papermaking has died a quiet death with the decline of the equipment and the lack of money to fix it. Katharine Nix will soon move to Queensland, and the equipment will sit, under wraps until a solution is found.

The institutional artists’ book is also taking a blow, at least in Canberra. Dianne Fogwell’s Edition + Artist Book Studio is winding up with a big flourish: a national tour funded by a Visions of Australia grant. We (for at this point I am working as Robin to Fogwell’s Batman) send the show to Mackay, Bathurst, Bunbury, Port Augusta, and Melbourne (Fogwell et al 2005). It is a hit, inspires many, gains fans, but is too late to save the studio, which is quietly absorbed by the Printmedia & Drawing Workshop and returns to being a simple institutional studio space. Ironically, the example of GIW and EABS has spawned other institutions to include book arts in their curriculum, not as separate classes but tucked into their printmaking courses.

Outside of the institutions, elsewhere in Canberra and the rest of the country, book arts are booming, especially in Queensland. There are now well-established practitioners who show regularly and teach workshops from their studios, like Adele Outteridge and Wim de Vos with their West Bank Studio in Brisbane. Artspace Mackay has been built, purpose-designed to house its collection of artists’ books (‘No one thanked me’, said the librarian bitterly when I later met her at a conference). First Director Robert Heather started an annual, later biannual conference called Focus on Books and a dedicated book award exhibition. The book awards still exist, but the conference fizzled out soon after Heather landed a job at the State Library of Victoria.

Back in Canberra, the private press movement has limped along with a new generation: Finlay Press (Ingeborg Hansen and Phil Day), who weren’t tied to tradition, mixing old technologies with new and eventually shifting into small mainstream publishing with Finlay Lloyd books; and myself, with my highly eclectic Ampersand Duck practice, started when the Edition + Artist Book Studio devolved.

Studio One limped along too, and was eaten by Megalo. The appointment of Alison Alder as Director in 2008 brought the organization full circle and injected it with a burst of energy (Wallace 2013). Comic book culture are still strong in Canberra, but coming up from behind are zines, small-run low tech physical publications that bring us full circle to the grass-roots publishing of the 1970s.

This brings us, with one more flashing leap, to now: 2014. We have only one trade bookbinder left in Canberra, and he’s getting old. Our offset printing industry has been exported to China. We do have lots of digital printers who like to play creatively, and there is an experimental inkjet facility at the art school. The Book Studio still exists, with me as its sole prophet. I teach book design and typography electives one day a week. Now that Alison Alder has moved to the School of Art, bring with her a commitment to collaboration and community involvement, the Book Studio may have a resurgence of activity. Megalo thrives, hosting a book workshop every six months (which is always full) and, with Ingeborg Hansen taking the reins, I am confident of its support of book culture. In a moment of enthusiasm that they may now be regretting, Strathnairn Arts Association has taken the papermaking equipment left behind by Katherine Nix. They are at that tender point of needing to put some capital into housing the equipment and are unsure that there is enough community support to make the investment worthwhile. Plans for paper workshops might kick it along a little, and I’m hoping to do this with my book classes.

Nationally, artist’s books are a stable genre. Artspace Mackay still has its Libris Award (but not its forum); there are new award exhibitions at Manly Gallery in Sydney and East Gippsland in Victoria, and a book can be submitted to pretty much any of the many regional works-on-paper competitions. Both SLQ and SLV have fellowships for artists’ book research and right now there are at least 5 PhD students at various stages focusing on aspects of artists books, from exploration into the haptic to the photobook. On top of that, it is such an accepted medium that artists are making books as a natural part of their practice or studies and do not know what to do with them once they’re made. This much has not changed: there are no dedicated galleries or destinations for artists’ books. There is one showcase online presence for Australian books: Artists Books 3.0, started by Robert Heather. There are few dedicated curators outside of the major institutions.

Aside from the institutional focus, book arts are still really popular around Australia, aided and abetted by the internet, the rise of scrapbooking (which put lots of great affordable tools on the market) and a drive to do something with our hands as a reaction to our increasingly disembodied digital culture. The comic and zine subcultures are strong in Canberra. The Canberra Craft Bookbinding Guild has a reputation for happily integrating traditional and alternative book structures, something that has caused great rifts in other guilds. Their annual exhibitions always include artists’ books. Despite there being no central educational focus other than my book electives, Canberra artists continue to make books, something I demonstrated last year when I curated a survey show of Canberra artists’ books to tie in with the centenary (2013).

If you think this sounds like the story of a golden era that declined, you would be right to some degree. Scholar Sasha Grishin has, in his work on artists’ books, continued to draw a line at about 1996, giving the impression that not much has happened in the region since then, and discounting the impact of short-term projects like Raft Press. I disagree. I think we’ve ticked along admirably, and we have all the ingredients to pump things up again. Earlier this year I opened an exhibition of papermaking at Strathnairn and tried to sound as rallying as possible to encourage them to keep the papermaking equipment and make that commitment to housing it properly.

Imagine, I said, pitching Canberra as a ‘City of the Material Book’, making it a destination for artists. We have all the components; we just need energy and support. We could combine forces, have a festival: a rolling series of workshops: paper at Strathnairn, image-making at Megalo, text production at the ANU Book Studio, bookbinding at CIT with the Bookbinding Guild. The complete book, made by hand. Imagine combining that with UC’s creative writers, getting the NLA involved with a related fellowship, co-ordinating the city’s galleries to run book-related exhibitions. Even if it happened only once, it would be amazing. Let’s go larger: imagine a centre of the material book, sited in a city that was big enough to attract serious scholars and makers, and small enough to make all these events happen regularly. Canberra has the history to support it.

Endnotes

1. This is a less formal version of a paper presented to the 2014 annual conference of the Bibliographic Society of Australia and New Zealand.

2. For further information about the workshop, see Herel, 1984, 1992, 1994.

3. Cardew herself only lasted until 1999, dying too young of cancer.

4. Just! Adobe released Pagemaker in 1984.

Agostino, M 2009 The Australian National University School of Art: A history of the first 65 years, Canberra: ANU School of Art

ANU Poets’ Lunch: http://www.anu.edu.au/emeritus/poets/index.html (accessed 30 October 2014)

Blast Magazine: http://www.austlit.edu.au/austlit/page/C277351 (accessed 30 October 2014)

Catalano, G 1983 The Bandaged Image: A study of Australian artists' books, Sydney: Hale & Iremonger

Hill, M 2007 ‘The Graphic Expression of the Lives, Obsessions, and Objections of Small Press Sick Puppies and Scat(ology) Cats: A short survey of some aspects of Australian alternative comics 1990-2000’ International Journal of Comic Art 9(1) Spring 2007: 411–437

Florance, C 2013 ‘One Hundred Years and On: 100% books by Canberra artists’, The Blue Notebook 8(1): 9

Fogwell, D, S Grishin, R McMaster, C Florance and D Williams 2005 How I Entered There I Cannot Truly Say: Collaborative works from the ANU Editions + artist book studio, Canberra: ANU School of Art

Ginninderra Press: http://www.ginninderrapress.com.au/ (accessed 30 October 2014)

Grahame, N, A Kirker and J A Hoffberg 1996 Artists' Books + Multiples Fair '96, Brisbane, Qld: Numero Uno Publications

Grishin, S 1994 ‘Canberra Printmakers, Printers and their Audience: Notes towards a history of printmaking in the ACT and surrounding region’ in N. Sever and D. Fogwell (eds) The Print, the Press, the Artist and the Printer: Limited editions and artists' books from art presses of the ACT, Canberra, ACT: ANU Drill Hall Gallery: 12-19

Herel, P 1984 Books: Graphic Investigation Workshop 1980–84, Canberra: Canberra School of Art

Herel, P 1994 Fragile Objects: Artists' books and limited editions (2), Graphic Investigations Workshop 1994, Canberra: Australian National University

Herel, P & D Fogwell 1992 Artist's Books and Limited Editions (1): GIW 1980–1992, Canberra: Canberra School of Art

Herel, P & D Fogwell 2001 Artists’ Books and Limited Editions: Graphic Investigations Workshop, catalogue raisonné, Volume 3, 1995–1998, Canberra: Australian National University

Hudson, M 1984 ‘Book Arts’ in K Lockwood (ed), Craft Australia Yearbook 1984, Sydney: Crafts Council of Australia 77-89

Mulini Press: http://www.austlit.edu.au/austlit/page/A36950 (accessed 30 October 2014)

Richards, M 1993 A Licence to Print: Alec Bolton and the Brindabella Press, Canberra: Friends of the National Library of Australia

Rogers, P & A Shannon & N Wootton 1984 First National Conference of Craft Bookbinders, Australia, Canberra: Craft Bookbinders' Guild, Incorporated

Sever, N & D Fogwell 1994 The Print, the Press, the Artist and the Printer: Limited editions and artists' books from art presses of the ACT, Canberra: ACT Drill Hall Gallery

SLQ Artists’ Books Collection: http://www.slq.qld.gov.au/resources/art-design/artists-books (accessed 30 October 2014)

‘Spare Times’ 1986, Canberra Times, 8 May 1986, 11

Toynbee Wilson, J 1984 ‘Paperwork’ in K Lockwood (ed), Craft Australia Yearbook 1984 Sydney: Crafts Council of Australia, 91-101

Wallace, C 2013 Megalomania: 33 years of posters made at Megalo Print Studio 1980-2013, Canberra: Megalo Print Studio + Gallery.