Despite moves towards inner-urban consolidation, Australian cities continue to expand in girth. In the process, housing development transforms formerly rural land into "peri-urban" settlements. These transitional zones are often sites of contestation: they place pressure on local amenities and infrastructure, reveal limitations in transportation and food systems, and conflict with “lifestyle” values. In this paper I explore these tendencies through the lens of an art project about Australian farmer P.A. Yeomans. Between 1940 and 1980, Yeomans developed a system of organic farming - "Keyline" - optimised for the poor soils and low rainfall of Australian conditions. Keyline has been hugely influential, particularly on the permaculture movement, which advocates re-localisation of food production in inner-cities. But Yeomans’ own farms, despite being praised as exemplars of “agricultural heritage”, are themselves in the process of being wiped out by medium-density housing developments.

Keywords: peri-urban - agriculture - housing - community activism - dialogical art

The Yeomans Project (2011-14), a collaboration between Ian Milliss and Lucas Ihlein, comprises multiple components: a blog, a newspaper publication, gallery installations, archival exhibits, a series of lithographic prints, and bus tours to farms on the outskirts of Sydney and Melbourne (Ihlein and Milliss 2013). The project embodies the recent turn to the relational and pedagogical in contemporary art production. This way of working places emphasis on social interaction and learning as aesthetic acts in their own right. The space for this mode of process-oriented creative practice has been opened up over the last 40 years, particularly through the work of conceptual artists – of which Milliss is himself a first-generation Australian example.

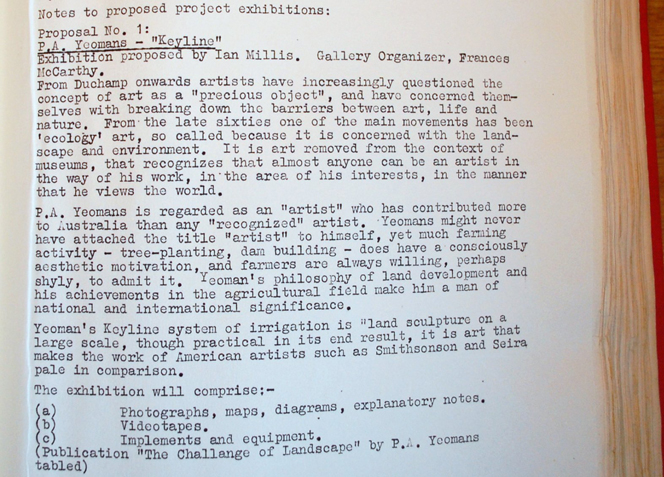

In the early 1970s, Milliss was beginning to formulate a definition of art beyond the standard notion of aesthetic objects housed within special architectural spaces. Alongside Australian philosopher Donald Brook, Milliss argued that artists were people who transformed culture in some significant way, and that such people could be found in any field – even agriculture (Brook 2012; Milliss 1973). In 1975, Milliss singled out P.A. Yeomans for particular attention, proposing that the Art Gallery of NSW host an exhibition by Yeomans, entitled Keyline, in their newly established contemporary art space. Milliss argued that Yeomans’ work in re-designing farm systems constituted a form of ‘land art’ more worthy of the name than the spectacular earthworks being constructed at the time by Heizer, Smithson, Morris et al. While these American avant-garde figures were using bulldozers to create spectacular landforms (and in the process expanding the definition of art) Yeomans' agricultural research offered an approach whose ethics of engagement ran much deeper. Yeomans demonstrated through his landscape experiments that by carefully ‘reading’ the land and designing accordingly, farms in drought stricken areas could respond positively to local climate, geology and topography. In other words, Yeomans initiated what we would now refer to as ‘sustainable’ agriculture for uniquely Australian conditions (Mulligan and Hill 2001).

While Yeomans’ work has since been acknowledged as a key influence on the development of permaculture, the Australian artworld in the mid-1970s was clearly not yet ready to present the experiments of a farmer within the art museum. Milliss’ proposal to the Art Gallery of NSW was rejected as unsuitable - on the grounds that it resembled an agricultural trade show, not art (Ihlein and Milliss, 2011). Recent developments in contemporary art practice, by contrast, have begun to articulate this sort of categorical ambiguity as part of a deliberate aesthetic strategy. The kinds of approaches to artmaking embodied in The Yeomans Project (discussions, tours, pedagogical events and so on) have been variously described as dialogical artmaking, relational aesthetics, critical spatial practice, or socially engaged art practice (Bourriaud 2002; Kester 2004; Bishop 2012). These artworks ride the boundaries of art and non-art. Working within the western avant-garde traditions of performance art and happenings, they also operate as public pedagogy, community activism, and even as a form of academic action research. Art theorist Claire Bishop has described such works as possessing a ‘double ontology’ (or, following Felix Guattari, a ‘double finality’). She writes, ‘[Socially engaged art projects] need to be successful within both art and the social field, but ideally also testing and revising the criteria we apply to both domains’ (Bishop 2012: 273).

Another way of describing this sort of practice is ‘1:1 scale art’, following the notion put forward by Stephen Wright (Wright 2012). When it operates at 1:1 scale, art does not represent the world in a separate, miniaturised version of itself, but rather participates in the world as it is, enabling a slightly shifted sensory and cognitive perception of reality. As Wright asserts (borrowing a metaphor from both J.L. Borges and Lewis Carroll) at 1:1 scale, art ‘use[s] the country itself, as its own map’. Wright offers half a dozen examples from a "disparate" array to show what art operating at 1:1 scale might look like. These include Walid Raad's Atlas Group Archive, Meshac Gaba's Museum of Contemporary African Art, and the journal Third Text, founded by Rasheed Araeen. All these projects operate as "real", full-scale instances of some other cultural entity (museums, archives, journals) and thus risk losing their sole identity as works of art. For Wright, this categorical ambiguity is not a defect. To the contrary, the "deliberately impaired coefficient of artistic visibility" of a 1:1 scale artwork "allows it to escape from the debilitating assignment to the ontology of art" (an impulse akin to Bishop's "double ontology").

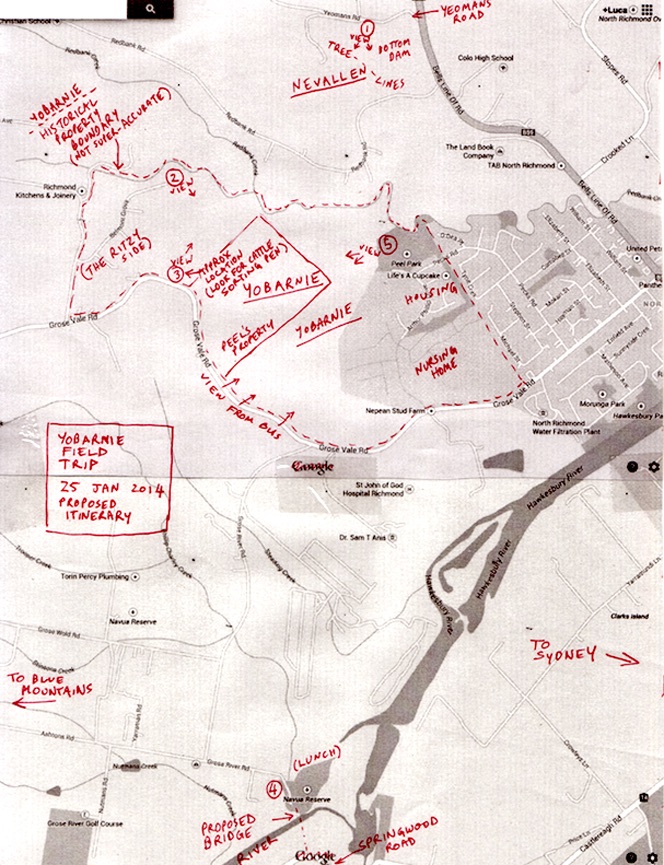

I offer these examples from Wright's provocative essay to show how the notion of "using the country itself as its own map" is a metaphor that can be applied across many different kinds of practices, and not only (as in the case of the Yeomans Project) within situations of territorial contestation where maps are quite literally deployed as legal tools. In what follows I want to reflect on one part of The Yeomans Project which I believe works at 1:1 scale: a field trip to Yobarnie, a former Yeomans property in western Sydney. This trip, by bus, took forty participants from the Art Gallery of NSW out to North Richmond, to experience for themselves a significant site within the history of Australian agriculture.

The Field Trip

Our bus departs the Art Gallery of NSW on a hot Saturday morning, on Australia Day weekend, 2014. Ian Milliss and I use the hour-long journey to get to know our group of about 40 punters, hailing principally from the artworld and permaculture communities. Some have a particular interest in ‘social processes as art’. Some are ‘VIPs’ - members of P.A. Yeomans' extended family and friends who have never had the chance to see Yobarnie for themselves, or haven't visited the place for more than 50 years. We explain our own enthusiasm for the work of P.A. Yeomans (Ian's going back to the 1970s, and mine beginning only a few years ago), and try to articulate how Yeomans’ practical research might operate as a utopian model for an expanded definition of art. Yeomans, we argue, attempted to transform (agri)cultural practices; aesthetic beauty emerged alongside an ethical engagement with the landscape. We also touch on some of the difficulties Yeomans had in ‘getting the word out’ during his own lifetime. The dissemination of his visionary organic methods was stymied by widespread federal subsidies encouraging the application of superphosphate fertilisers. Furthermore, Yeomans’ own techno-evangelical mode of communication sometimes proved counterproductive.

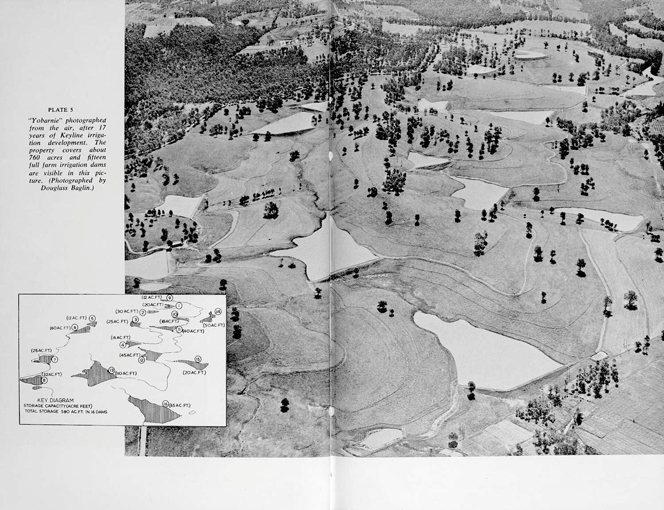

Yobarnie is the site of one of P. A. Yeoman’s earliest experiments in Keyline agriculture. Our trip here is a pilgrimage of sorts. It was at Yobarnie (and neighbouring Nevallen) that Yeomans, after much trial and error, struck upon his method of creating a series of strategically located dams, linked together by flow channels running along the contours of the land (Macdonald Holmes et al 1950). It's an ingenious system - so simple and smart it seems strange that it took until nearly 1950 for agriculture to come up with it: catch the water where it falls using a dam high up in the landscape; allow it to slowly make its way towards the creek line, storing it along the way in a string of connected dams; and use the water as it travels downhill to irrigate the land. Gravity does all the work: there's no need to pump water back uphill from the river system. The soil biology is enriched in the process, and the farm exports high value organic beef (Yeomans 1954).

Today's Field Trip to Yobarnie is the second of our publically advertised bus tours. The first, in 2011, visited Ben Falloon and his family at Taranaki Farm on the outskirts of Melbourne (Ihlein and Milliss 2011a). Falloon had taken over his father's conventionally-run cattle farm and was in the process of transitioning it to a Yeomans-inspired Keyline system. It was a joy to witness his enthusiasm for what has become known as ‘regenerative agriculture’ - a form of farming which builds soil and creates capital in the land rather than depleting its minerals (RegenAG 2015). Taranaki Farm is a good news story. The Yobarnie tale, by comparison, is disquieting. As early as 1964, only 20 years after acquiring the land, P.A. Yeomans was forced to sell it to pay death duties when his first wife Rita died. Since that time, the property has been continually farmed, but its subsequent owner did not maintain it along Yeomans' Keyline principles. Despite this, many of the positive developments P.A. Yeomans implemented in the 1950s and 60s - dams, water channels, and tree belts - are still remarkably functional. And it's the remnants of these developments that our travellers have come to witness today.

Field Days

Throughout the 1950s and early 60s, P.A. and Rita Yeomans, and their sons Neville, Allan and Ken regularly threw open the doors of Yobarnie to the public. The Yobarnie Field Days, as they were called, were an opportunity for P.A. to share his experiments in-situ - exceeding the bounds of the two dimensional graphics and textual descriptions in his numerous (mainly self-published) books, brochures and magazines. Almost every week, farming families, soil scientists, and representatives from government and industry would make their way to Yobarnie (and the neighbouring Yeomans property Nevallan) to witness the Keyline system in action. Black and white photographs document dapper farmers in tweed jackets and wide brimmed hats looking on as P.A. opens a water valve, allowing gravity to inundate a paddock via his patented ‘Flood-flo’ irrigation system. In her foreword to The Keyline Plan (1954), P.A.'s first wife Rita gives an insight into the strategic position of Yobarnie on the outskirts of Sydney. Attendees of the Field Days, she writes, were often entranced by what they saw:

[they] arrive for a quick inspection, checking their watches on arrival and allotting perhaps a fifteen minute ‘stay’. These people usually are on their way from the city to their inland properties and the visit to our place is to be ‘just a passing look’. They generally remain for hours. (Yeomans 1954)

Our Yobarnie Field Trip, then, is something of a re-enactment of events taking place more than 50 years ago. The difference, however, is that rather than showcasing an exciting possible future for agriculture, our trip has sober undertones. Yobarnie has recently been approved for redevelopment as medium density housing. Within a few years, as many as 1500 single-story homes may occupy this land, wiping out its agricultural heritage.

Yobarnie and Peri-Urban Politics.

For me, the Yobarnie Field Trip was originally planned as a means for learning more about P.A. Yeomans' farming and landscape design techniques. Comparing my experience on previous farm trips with the experience of reading Yeomans' books, I knew that walking the topography of the land was a powerful heuristic. And yet, as the day of our Yobarnie trip approached, I became increasingly aware that agricultural design was going to be just one of the things we would be learning about. The other, and perhaps more pressing issue, was the politics of rural space and urban development.

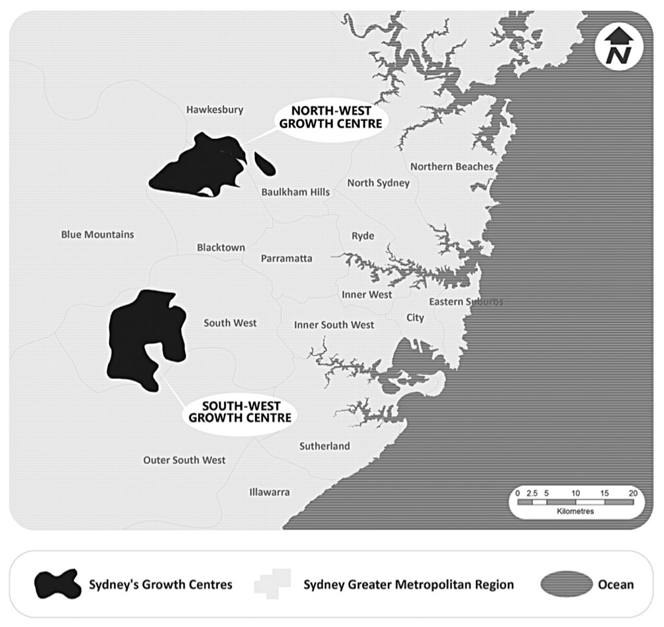

In a recent article examining the use and value of land on the outskirts of Sydney, geographer Sarah W. James argues that peri-urban agricultural zones have often been treated with scant regard by government planning departments (James 2014). They are in-between spaces, undervalued as places in their own right, seen merely as sites of future housing and commercial development. Peri-urban sites, James explains, are considered ‘transient’, in the sense that their eventual transition away from agriculture is accepted as inevitable, and even encouraged via the state government’s incentives to release new land for housing in response to rising urban population:

In the 2005 Metropolitan Strategy, the majority of new greenfield development was in two Growth Centres in the north- west and south-west of Sydney, where the majority of Sydney’s vegetable farms were located. (James 2014: 380)

In fact, it is the ongoing surge in property values which is putting pressure on owners of agricultural land to subdivide, sell off, or develop. The per-hectare proceeds of fruit, vegetables, beef or egg production on the outskirts of Sydney cannot possibly compete with the return on investment offered by housing development. And yet, ironically, it is precisely the bucolic proximity to those few remaining agricultural sites which is attractive to potential home-buyers.

This is the broader social, geographic and economic context in which Yobarnie is currently situated. On our Field Trip, we are addressed by members of the North Richmond and District Community Action Association (NRDCAA), who actively oppose the rezoning of Yobarnie as 1500 medium density home sites (NRDCAA 2015). As we learn, the group has been working for more than five years on this project. One angle of attack has been to lobby for the land to be listed under the NSW state heritage register. Despite eventually succeeding in this campaign, the heritage listing has only slowed down - not halted - the development process. The coming estate, marketed as ‘Redbank’ will be required to make some design changes to acknowledge the significance of P.A. Yeomans’ Keyline system - but these will be relatively minor concessions in an otherwise standard housing in-fill scheme. What’s more, the NRDCAA has compiled exhaustive data showing that there is insufficient civic infrastructure in place to accommodate the influx of new residents. Without wholistic, well-planned upgrades (which do not seem to be forthcoming) water, roads and sewerage will all be placed under major stress. Still, the development goes ahead.

When our bus stops on the main road, high above the top dam at Yobarnie, we look down onto the rolling green pasture, and process all this information. Colorbond roofs, garage doors, manicured lawns, cul-de-sacs and queued traffic are mentally overlaid on the green fields, dams and disused irrigation channels. Even though we understand the fundamental economic logic of why Yobarnie must become Redbank, the sense of injustice at this transformation is palpable in our group. This feeling begins as an undercurrent, growing in volume as the day progresses. And so later, when the opportunity presents itself, at the encouragement of a disgruntled local resident, we trespass en-mass onto Yobarnie through an unpadlocked gate at the bottom paddock.1

The affective experience of this group-transgression is intoxicating.We spread out, scattering across the green field in groups of two or three. There is no sense that Milliss and I are any longer ‘in charge’. We are participants in an event that we have organised, but we have no privileged knowledge or authority about what happens next. This is no longer a tour. We have brought our ‘tourists’ to this place, and have framed the situation in terms of geography, economics and agriculture. But in choosing to illegally occupy Yobarnie, even temporarily, we are each implicitly voicing our opposition to the next step in its transformation. Walking on the land, some of us report feeling lost, or ‘at sea’ - there is no clear itinerary. And so we wander until we find remnant Keyline water channels, dams or contour tree lines, follow these along, beginning to piece together the logic of the landscape’s design at 1:1 scale. These remaining legible aspects of Yeomans’ agricultural ingenuity seem to possess some quality of the relic; there is an archaeological aspect to this experience. For students of permaculture, this is as close as you get to ‘holy land’. Some of the trespassers sit down - just to be with the place for a while.

Our occupation of Yobarnie (now officially fenced off as a construction site) is quietly thrilling, and the activity seems justified under an alternative moral code - a system of value which sits apart from the logic of real estate and property investment. There’s a romance to it - there’s no denying that. And it lends each of us a personal relationship to the place: powerful embodied experience trumping the detached transmission of information about the place. But there is, of course, something significant missing in all of this. Yobarnie’s heritage value as agricultural land only goes back sixty years. What was here before? How, if at all, do Indigenous histories and relationships to this country connect with this discourse of peri-urban politics?

Our Field Trip includes a stop at a place not far from Yobarnie called Navua Reserve. This is a convenient spot for our punters to have a toilet break and a picnic, and there’s sufficient space for the bus to turn around. But Navua Reserve is significant on a deeper level. It’s the site of a sort of sandy river-beach, an important local recreational resource. It’s also threatened with oblivion. Here, according to one council/state development proposal, a major bridge could span the junction of the Grose and Hawkesbury Rivers in order to carry all the extra motor traffic created by the Redbank development. One of our group, Naomi Parry, knows this place. She is an historian who has chronicled Aboriginal connections to Navua Reserve - or Yarramundi, as it is traditionally known. A few months after the Field Trip, Naomi sent us an email detailing a fragment of her research. We posted this on the Yeomans Project blog alongside photographs of our Field Trip (Ihlein and Milliss, 2014). Her account presents a completely different side to the discussion around Yobarnie’s provenance. I quote here from Parry’s text at length to give a sense of the complexity of Aboriginal-European relations that gave rise to the eventual transformation of land use in Western Sydney. She writes:

To me this place is Yarramundi, a favourite summer destination for people from Richmond, Penrith and the Blue Mountains. It's a bit scarred at the moment as it's had a lot of water flowing through it, but it's a beautiful soft place, of riverstones and clear water.

The name Yarramundi, which really belongs to the locality, is in honour of a man of the Boorooberongal Clan of the Dharug. Europeans referred to him as Chief of the Richmond Tribes, but he was a doctor, or wise man. Sometimes he is called Yellomundee, as he is in Watkin Tench's 1793 Complete Account of the Settlement of Port Jackson. Tench tells us that Yarramundi and his father Gomberee, another wise man, met with Governor Arthur Phillip on 14 April, 1791, just three years after the settlement began at Sydney Cove.

Almost exactly two hundred years to the day before our visit [to Yobarnie], on 28 December 1814, Yarramundi met with another Governor, Lachlan Macquarie, and handed over his nine-year old daughter, Maria, to the care of the Native Institution, then at Parramatta. It is through her that I know the history of this place, as I wrote her story in 2005 for the 'Missing Persons' supplement to the Australian Dictionary of Biography (Parry 2005).

Maria was remarkable for her ability to navigate white society without eschewing her familial bonds or her Aboriginality. In 1819 The Sydney Gazette reported that an Aboriginal girl of 14, thought to be Maria, had won first prize in an anniversary examination, ahead of 20 other pupils from the Native Institution and 100 white pupils. In 1822 she had married Dicky, the son of Bennelong, but he sickened and died the following year. By then she was living at the new Native Institution site at Blacktown and in 1824 met and married a white convict carpenter, Robert Lock. As a convict he was assigned to her: an inversion of traditional patriarchal and racial relations.

In 1831 she did something no Aboriginal person had ever done. She petitioned Governor Darling for land that had been granted to her late brother Colebee, which was sited next to the Native Institution. Colebee had received the land as a reward for working with Nurragingy on an ultimately abortive mission, tracking Aborigines with Macquarie's men, in 1816. Maria now claimed it, citing her relationship to Colebee, as a daughter of Yarramundi. She received a grant at Liverpool where she was living but she was resolute on the Blacktown land and was finally able to claim it in 1843. It was, in many respects, the first native title claim in Australian history.

Maria and Robert lived well and long and had nine children. The land at Blacktown was lost to the extended family in the 1920s, but some of it and the Native Institution site remains contested. Their legacy, and Yarramundi's, is in the family they created: up to 7,000 descendants, many of whom still have links with Greater Western Sydney, and identify as Dharug. The Deerubbbin Land Council are active in managing sites like Navua Reserve, and the rivers of the area.

It was a happy and beautiful accident that Ian and Lucas picked Navua Reserve for lunch. It is a fine place to think about land, and how the sense of it, and relationships, run through time. (Ihlein and Milliss 2014)

As a model for socially engaged art practice, the Yeomans Project Field Trip creates a framework which can accommodate an unhomogenised array of different experiences. In a precedent project, the Redfern Waterloo Tour of Beauty (2005-9), I worked with artist group SquatSpace organising a bus and bike tour of the inner Sydney suburbs of Redfern and Waterloo (Ihlein 2015; Vincent 2006). Much like Yarramundi, the Redfern area has long been the site of intense contestation. It sits on the fringe of the CBD, home to strong and visible indigenous, public housing, and immigrant communities. Now, the inexorable transformative pressure of gentrification makes these communities seem more precarious than ever. Like SquatSpace's Redfern tour, our Yobarnie Field Trip allows all of these uneasy matters to sit together in a state of prolonged irresolution. The format - borrowed from countless cheerful commercial tourist bus tour operators around the world - is in this case détourned. Together, we undergo a disquieting and problematic experience at 1:1 scale within a complex environmental and social situation.

Epilogue

Several months after the Yobarnie Field Trip, some surprising news came to light. The Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC) began investigating Bart Bassett, the state Liberal MP for Londonderry (the area which encompasses North Richmond) (Ihlein 2014a). In 2010 Bassett had accepted an $18,000 donation from Buildev, the property developer in charge of the Redbank project. This donation may have influenced the fast-tracking of the approval process for Redbank’s medium density housing development (Winestock 2014). Bassett subsequently resigned from the Liberal party, and local residents have successfully lobbied the Hawkesbury Council to put a hold on all developments at Redbank, while the ICAC investigation continues (Kidd 2014).

Endnotes

1. Prior to our Yobarnie Field Trip we contacted the developer, North Richmond Joint Venture (NRJV) requesting to physically access the land (now fenced off as a building site, and emblazoned with 'no trespassing' signs). We also requested that a representative from NRJV join us on the Field Trip to speak about the housing project from the point of view of the developers. NRJV refused both requests.

Bishop, C 2012 Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship, New York: Verso

Bourriaud, N 2002 Relational Aesthetics, Dijon: Les Presses du Réel

Brook, D 2012 ‘Experimental Art’ Studies in Material Thinking Vol.8 at http://materialthinking.org/papers/101, accessed February 4, 2015

Ihlein, L and Milliss, I 2011 ‘In the Archives with Lucas’ The Yeomans Project 11 August 2011 http://yeomansproject.com/in-the-archives-with-lucas/ (accessed January 4, 2015)

Ihlein, L and Milliss, I 2011a ‘Field Trip!’ The Yeomans Project 1 November 2011 http://yeomansproject.com/field-trip/ (accessed February 4, 2015)

Ihlein, L and Milliss, I 2013 The Yeomans Project http://yeomansproject.com (accessed January 4, 2015).

Ihlein, L and Milliss, I, 2014, ‘Field Trip to Yobarnie’ The Yeomans Project 4 April 2014 http://yeomansproject.com/field-trip-to-yobarnie/ (accessed February 4, 2015)

Ihlein, L 2014a, ‘A heritage vision for sustainable housing goes to ICAC’ The Conversation 2 September 2014 https://theconversation.com/a-heritage-vision-for-sustainable-housing-goes-to-icac-21616 (Accessed February 4, 2015)

Ihlein, L 2015 ‘Redfern Waterloo Tour of Beauty’ http://lucasihlein.net/Redfern-Waterloo-Tour-of-Beauty-1 (accessed February 4, 2015)

James, S.W. 2014 ‘Protecting Sydney’s Peri-Urban Agriculture: Moving beyond a housing/farming dichotomy’ Geographical Research 52:4, 377-386

Kester, G 2004 Conversation Pieces: Community and communication in modern art, Berkeley: 2004

Kidd, J 2014 ‘Hawkesbury council wants housing proposal at centre of ICAC probe put on hold’ ABC News September 10 2014 http://www.abc.net.au/news/2014-09-10/hawkesbury-council-wants-housing-proposal-put-on-hold/5733100 (Accessed February 4, 2014)

Macdonald Holmes, J., Devery P.J. and Yeomans, P.A. 1950 ‘The ‘Yobarnie’ methods for soil and water conservation’ Australian Geographer, 5:8, 15-22

Milliss, I 1973 ‘New Artist’ in Object and Idea exhibition catalogue at http://milliss.com/new-artist/ Melbourne: National Gallery of Victoria (Accessed February 24, 2014)

Mulligan, M and Hill, S 2001 Ecological Pioneers: A social history of Australian ecological thought and action, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

North Richmond and Districts Community Action Association Inc (NRDCAA) 2015, http://nrdcaa.blogspot.com.au/ (accessed February 4, 2015)

Parry, N 2005 ‘Lock, Maria (1805-1878)’ Australian Dictionary of Biography http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/lock-maria-13050 (accessed February 4, 2015)

RegenAG 2015, ‘About RegenAG’, at http://regenag.com/web/about-us.html (accessed February 4, 2015)

Vincent, E 2006 ‘Tour of Beauty: Exploring a Sydney art-collective's new enterprise in the deeply divided inner-city area of Redfern-Waterloo’ Meanjin 65:2, 121-138

Winestock, G 2014 ‘Tinkler's secret $18,000 donation to NSW Liberal campaign exposed at ICAC’ Hawkesbury Gazette August 25, 2014 http://www.hawkesburygazette.com.au/story/2511179/tinklers-secret-18000-donation-to-nsw-liberal-campaign-exposed-at-icac/ (Accessed February 4, 2015)

Wright, S 2012, ‘‘Use the country itself, as its own map’: operating on the 1:1 scale’ North East West South 22 October 2012, at http://northeastwestsouth.net/use-country-itself-its-own-map-operating-11-scale (accessed February 4, 2015)

Yeomans, P.A. 1954 The Keyline Plan, Sydney: Yeomans http://www.soilandhealth.org/01aglibrary/010125yeomans/010125toc.html (Accessed February 4, 2015)

Yeomans, P.A. 1958 The Challenge of Landscape: the development and practice of Keyline, Sydney: Keyline Publications http://www.soilandhealth.org/01aglibrary/010126yeomansII/010126toc.html (Accessed February 4, 2015)

Yeomans, P.A. 1965 Water for Every Farm. Sydney: K.G. Murray

Yeomans, P.A. 1973 Water for Every Farm: A practical irrigation plan for every Australian property Sydney: K.G. Murray